Anybody who has ever attended or worked at the University of British Columbia’s Vancouver campus knows that it is not actually part of the City of Vancouver – despite the fact that its mailing address clearly states “Vancouver”. Together with the University Hill neighbourhood and Pacific Spirit Regional Park, it actually forms an “unincorporated area” – part of Electoral Area A within the Metro Vancouver Regional District.

Electoral Area A, commonly known as the “University Endowment Lands” or UEL, is subject to several overlapping jurisdictions: Metro Vancouver, the provincial government, Musqueam First Nation, and of course UBC itself. However, there is nothing that can be considered an elected local government, answerable to people who live and/or work there. The resulting governance situation can be confusing for students, residents, and businesses alike.

However, this was not always the case. In fact, it is likely that few people know the historical circumstances that led to this situation. Those circumstances centred, as so many things do in Vancouver, on money, real estate, and politics – and the issue was decided by the votes of only a few hundred local residents.

Vancouver as originally incorporated in 1886 included only the areas immediately south of Burrard Inlet and around False Creek. Its southern and western boundaries were what are now 16th Avenue and Alma Street, respectively. The lands beyond those boundaries – still covered in old-growth or second-growth forest except for scattered farms and homesteads – remained unorganized.

In 1892 the District Municipality of South Vancouver was established, extending west of Boundary Road (Burnaby) and south of Vancouver. It was also defined as enclosing the land “along the low water mark” of the North Arm of the Fraser River and the south shore of English Bay, including Point Grey itself.

In 1908 South Vancouver was divided roughly in half, at what is now Cambie Street. The western part was incorporated as the Municipality of Point Grey, and included “all of that portion of the said present Municipality of South Vancouver lying west of the line of division”.

In 1910 a provincial University Site Commission selected the western end of Point Grey as the site for the proposed University of British Columbia. In response, the government reserved 175 acres from their extensive Crown land holdings in that area of the Municipality of Point Grey for UBC’s future home. The Province also reserved about two million acres in the interior of British Columbia as a source of financial support for the university. Proceeds from the sale of these lands were to be used to fund its construction and maintenance. However, it was soon discovered that the reserved lands did not have enough value to ever provide significant revenue. The government eventually exchanged the original endowment for about 3000 acres adjacent to the Point Grey site. Both the university site and the surrounding University Endowment Lands were Crown land owned by the Province, but still located within the municipal boundaries of Point Grey.

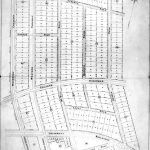

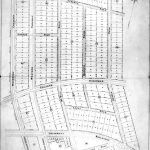

Vancouver Map and Blueprint Co. Ltd. (1910). [Map of Point Grey showing proposed streets on future UBC campus site – cropped]. UBC Rare Books and Special Collections.

From an early date the Municipality had high hopes for the development of the Point Grey lands. A map dated 1910 shows a proposed network of roads extending westward to the end of Point Grey, culminating in a park or “Village Green” near the site of today’s Rose Garden. Beginning in 1909 the town had campaigned for the University Site Commission to consider the area for the site of UBC’s campus. A petition that year asked municipal council to borrow up to $375,000 to build roads and other infrastructure to serve the lands around the point if the Commission chose that area (

Vancouver Sun, 19 January 1929).

Construction of the campus began in 1914, but was suspended at the outbreak of the First World War, and further delayed by financial shortfalls and government inaction. UBC opened its doors in 1915 at the “Fairview campus” near Vancouver General Hospital. It took a 1922 student publicity campaign, culminating with the “Great Trek” parade and the presentation of a petition with 56,000 signatures, to convince the provincial government to renew construction at Point Grey.

The following year, the Province began planning the development of the UEL for sale as residential properties. Lots had to be surveyed; roads, sewers, and other infrastructure had to be built. The question of how to pay for this work soon became a source of tension between the Province and the Municipality of Point Grey.

During the 1923 Point Grey municipal elections, George A. Walkem of the UBC Department of Mechanical Engineering ran for the position of reeve (equivalent to mayor). Walkem’s position was that the Province “should develop the grounds … and on completion turn the entire site over to the municipality, debt free”. He cited the development of Shaughnessy by the CPR, which turned over the high-end neighbourhood to Point Grey upon completion, as a precedent (Vancouver Sun, 5 January 1923). Walkem insisted that once the University was established at Point Grey the surrounding lands would increase in value, so that their sale would pay off any debt incurred from developing the area (Vancouver World, 10 January 1923). Walkem would go on to win election and serve as reeve for two years.

In a meeting with Point Grey municipal council on November 19, 1923, Provincial Engineer E.A. Cleveland outlined the provincial government’s own plans. According to Cleveland, about 100 acres had already been cleared and made ready for the necessary improvements. He told the council that this initial offering was “an experiment on the part of the government”. If it was successful, further tracts within the UEL would opened up in a similar manner.

Scrapbook #16, p. 31 (November 1923). [Newspaper clippings from Vancouver “World”, “Province”, and “Sun” regarding development of University lands]. UBC Scrapbook Collection. University of British Columbia Archives.

Contrary to what Reeve Walkem had suggested, Cleveland explained that the cost of those improvements would ultimately be borne by the buyers of the building lots through their property taxes. However, the immediate financing of that work had to be addressed. It was eventually agreed that the provincial government would continue development of the site and finance all improvements. Point Grey would take them over upon completion and reimburse the Province for the work, issuing bonds to raise the money. The Municipality could then assess a local improvement tax on those properties to retire the bonds.

However, the Province insisted that assessments on the built lots not be raised for an extended period. The government’s concern was that the UEL lots were likely to be of higher value than other properties. Assessed at a higher rate, they would carry a disproportionate share of costs of other municipal improvements, and so be less attractive to buyers. Point Grey council, however, did not want this limitation imposed, arguing that “the provincial government should not expect an artificially-low tax assessment for its buyers when such a privilege was not open to the ordinary ratepayer” (Vancouver World, 20 November 1923).

Apart from toney Shaughnessy, the neighbourhoods known today as Kerrisdale, Marpole, and West Point Grey, and a few farms, most of the Municipality consisted of undeveloped land which generated no tax revenue. With such a narrow tax base, the council did not want to be made responsible for new local infrastructure that it could not pay for. The provincial government also saw this, and suspected that Point Grey would eventually treat the UEL area as a “cash cow” supporting the entire municipality.

By the spring of 1924 the assessment question still threatened to block a final agreement. Minister of Lands T.D. Pattullo was quoted in the Vancouver Sun on April 12 saying “that the new subdivision cannot pay for all its own improvements and also be saddled with the cost of improvements in other parts of the municipality is [a position] that we cannot very well recede from…”. He then hinted at a possible consequence of not reaching an agreement:

Our only alternative would be to establish a new municipality, which, of course, we do not wish to do.

The suggestion that UBC and the lands surrounding it could be carved off from Point Grey caught the imagination of at least one editorial writer at the Sun:

To permit the formation of a Greater Vancouver without embarrassment and hindrance, Government and University holdings in Point Grey should be created into a separate municipality to be known as University Municipality….

It would take years to develop this tract of land under Point Grey government, because Point Grey is an expansive municipality with troubles of its own.

Separated from Point Grey, this tract could be developed by the University and the Government in a manner that would yield most profits from this area which will be a future important residential section of Vancouver. (Editorial, Vancouver Sun, April 16, 1924)

Frank, Leonard (26 March 1929). [View of University Boulevard after paving and landscaping]. UBC Archives image UBC 1.1/117

Negotiations dragged on through the spring and summer. In August Pattullo issued a statement reiterating the government’s stance, and repeated his threat to remove the University and the UEL from Point Grey if no agreement could be reached.

By this time the improvement work was nearing completion. On 108 acres, containing the first 100 lots to be sold, about 26 miles of pipe for water, sewers, and drains had been laid, with connections up to the property lines of every lot. Contracts for paving 2 ½ miles of road and 1 ½ miles of sidewalk were about to be awarded, and that work would be done within six weeks. According to Pattullo, immediately upon completion of the paving, those 100 lots would be put on the market so that “purchasers may have their homes built by the time the University opens its new home” the next year (Vancouver Sun, August 19, 1924).

Minister Pattullo and Provincial Engineer Cleveland met with Point Grey council on August 29 in an attempt to reach a final decision. When newspapers reported on the meeting the next day, it was obvious that while the assessment question had been side-stepped, the main issue – that the UEL properties could not be exploited to support improvements elsewhere in Point Grey – had been settled in favour of the Province. Both sides publicly agreed that neither the Province nor the eventual purchasers of the improved UEL lots would assume any of the Municipality’s current financial obligations. Whatever taxes or fees might come from from the UEL properties, regardless of their assessment, would not go towards those old debts. The neighbourhood would be responsible only for its own improvements and for its share of the general cost of Point Grey’s municipal administration.

However, conflict re-emerged when the government introduced the Point Grey and District Lot 140 Agreement Act to the legislature in December. The proposed act called for Point Grey to take over the administration of the entire UEL – some 3000 acres – rather than just the land currently being readied for sale. Also, the Province would have the power to put on the market any additional amount of land without municipal consent. Finally, the legislation included a clause that empowered the government to take those lands (officially known as “a portion of District Lot 140, Group 1, New Westminster District”) out of Point Grey entirely if the Municipality objected to the government’s terms.

Scrapbook #16, p. 134 (March 1925). [Newspaper clippings from Vancouver “Province” and “Sun” regarding removal of University lands from Point Grey]. UBC Scrapbook Collection. University of British Columbia Archives.

Point Grey council saw these as unilateral changes to the deal they thought they had reached with the Province. They feared that the immediate transfer of such a large area would be a burden to Point Grey ratepayers. Council insisted that they would only take control of the 108 acres initially intended for sale, with the rest to remain as Crown lands until they were similarly ready for the real estate market. Based on their conversations with the Provincial Engineer the previous year, they had assumed the plan was intended as an “experiment” to test public demand for those properties, and that further negotiations would be necessary to decide how to dispose of the remaining lands.

There was no provision for Point Grey residents to approve this deal through election or referendum. Feelings ran so high, however, that a referendum was scheduled for March 28, 1925. The question was put to voters: were they for or against the transfer of the UEL from the Crown to municipal administration on the government’s terms? Minister Pattullo and the British Columbia government stood firm: vote yes, or the Municipality of Point Grey would lose the University, the UEL, and ironically the geographical Point Grey itself.

The government’s threats had no effect, as the proposal was rejected in a landslide vote of 860-264. It was one of eleven measures submitted for approval that day, all of which were rejected – it is possible that the voters of Point Grey were simply of a mind to say “no” to everything. However, regarding the University lands question it is almost certain that the heavy-handed approach of the provincial government played a role as well.

The government lost no time in responding: Minister Pattullo made it clear that the Province would take the UEL out of Point Grey. However, they would administer it as an unorganized territory.

While it was never said outright, the decision not to immediately set up a new municipality was likely due to the immediate need to upgrade the area’s water supply. According to Minister of Public Works W.H. Sutherland:

The [water] pressure at the University is now so low that it affords no fire protection at all…. We have to pay an abnormally high rate on our insurance. We … shall probably have to put in a storage tank, acquire fire fighting apparatus including pumps, and organize a volunteer fire brigade among the students and employees. We can not afford to have a disastrous fire in the new University buildings. (Vancouver Evening Sun, March 30, 1925)

This was a time-sensitive priority, for the sake of the University facilities still under construction as well as for the building lots that were due to go on sale on May 1. It was likely simpler for the Province to deal with this directly, without any additional political distractions.

The idea of a new municipality still had some public support:

“Students Wish to Establish Town in Wesbrook’s Memory…”

[S]tudents who have been wishing to find some way of commemorating the memory of the late Dr. Francis Fairchild Wesbrook will now likely turn their attention to a plan asking the provincial members to form a new municipality called Wesbrook, B.C….

Already several members of the Alumni Association have expressed their willingness to support the movement…. (Evening Sun, March 30, 1925)

“VARSITY MAY RULE DISTRICT”

“Rejection of Pt. Grey Pact With Gov’t May Result in Novel Municipality Being Formed”

A university municipality with undergraduate mayor and undergraduate councilmen may result from the Point Grey voting Saturday, the ratepayers of that municipality having turned down the University Lands Agreement submitted by the government….

[It would give] students a chance to obtain practical insight into civic administration…. (Vancouver Star, March 30, 1925)

BC Department of Lands (1926). University Endowment Lands … Plan showing General Arrangement of Blocks and Roads [map]. UBC Archives image 1.1/569-2.

Some commentary was more satirical in nature:

The New Municipality

By P.W. LUCE

… No man will be allowed to vote unless he holds the degree of Bachelor of Arts. Votes of money by-laws will be confined to Masters of Arts. Men who hold two or more degrees may vote two or more times, but in no case will absent-minded professors be allowed to vote for last year’s candidates at next year’s election….

All newcomers into the municipality will be considered as freshmen ratepayers, and must be initiated, before casting a ballot. Those who object will be taken to the westerly boundary and shoved off into the saltchuck….

Whenever there is a surplus in the treasury the professor of mathematics who happens to be treasurer that year will be requested to go through his books carefully and find out how the mistake occurred. If there has been no mistake and there really is money on hand, the shock will probably kill all the members of the council, and a beautiful experiment will come to an untimely end. (The Province, March 30, 1925)

Official confirmation of the Province’s intentions came in a letter from Pattullo to Point Grey council on April 8, which read, in part, “I beg to inform you that it is the intention to withdraw the University lands from the confines of the Municipality of Point Grey”. A provincial order-in-council would later set the new boundaries at Camosun Street, 16th Avenue, and Blanca Street.

Responses from council were low-key and tinged with regret, but the general feeling was that it was all the government’s doing and it was out of their hands. “I regret that the Government has taken this course,” councillor T. B. Bate was quoted in the Morning Sun on April 9. “Undoubtedly, had the Government given Point Grey anything like an equitable agreement, I feel sure that the residents of Point Grey would, without the slightest hesitation, have taken over this area, and that it would have been in the best interests of all parties concerned. But the agreement, as it stood, was absolutely detrimental to the interests of taxpayers”.

BC Ministry of Forests, Lands & Natural Resources (1923). University Endowment Lands Plan of Unit No. 1. UBC Archives image UBC 1.1/569-3

Ironically, considering that it was the selection of Point Grey as the site of UBC’s permanent campus that spurred the residential development of the area, the University administration had little involvement in this dispute. No recorded public statement regarding the matter was ever made by President Leonard Klinck, or (apart from George Walkem during his 1923 election campaign) by any other University official.

Also, almost no discussion of the matter was noted in the minutes of the UBC Board of Governors – the governing body responsible for property and business affairs of the University, and therefore the body presumably most directly concerned with the political status of the Point Grey lands. One exception is recorded in the minutes of the meeting of 31 March 1924, when the Board approved sending a letter to Minister Pattullo “in regard to placing reserve on University site and adjacent lands”. While this is vague, it might have been in connection with Pattullo’s suggestion of 12 April to create a separate municipality if no agreement could be reached. Almost exactly a year later, on 30 March 1925 the Board approved a map submitted by Provincial Engineer Cleveland “showing the changes in the boundaries of the University site”. Almost certainly this map was intended to show the areas to be separated from Point Grey Municipality.

Royal Canadian Air Force (19 September 1925). [Aerial view of Point Grey showing new UBC campus (right) and early development of UEL Lot No. 1 (centre)]. UBC Archives image UBC 106.1/197.

The UBC campus and the UEL were placed under the control of the Department of Lands, which would carry out the Province’s development plans. Lots on the first 108-acre unit – part of today’s University Hill – were placed on the market in May. Two years later, lots in a second subdivision of 83 acres were offered for sale. However, by 1930 the costs of surveying and servicing University Hill had outstripped the demand. UBC never saw any money from those sales – the revenue went towards debt retirement and general operating expenses. Development slowed during the Depression, and the last remaining lots were not sold until well after the Second World War.

For its part, Point Grey merged with the City of Vancouver in 1929. The University lands remained separate, and are still separate to this day. There is no municipal government. The University now controls most of what happens on the campus itself and the residential areas immediately surrounding it – collectively known as “University Town” – with input from the University Neighbourhoods Association. University Hill and the “University Village” mini-mall on University Boulevard are still part of the UEL, governed by the Regional District and with services provided by the provincial government and paid for with residential and commercial taxes. Local schools are governed by the Vancouver School Board. Finally, as it is part of their traditional un-ceded territory, Musqueam First Nation has an increasing amount of influence on how the area is developed and governed, especially with their leləm̓ neighbourhood now nearing completion. There is no local government, and the overlapping jurisdictions can be confusing for residents and businesses alike.

Frank, Leonard (26 March 1929). University Endowment Lands streetscape. UBC Archives image UBC 1.1/651-2

Occasionally, the idea to form a new municipality is brought up again. However, residents voted against it in a 1995 referendum. Apart from a detailed proposal published in The Ubyssey student newspaper in 2011, no other serious attempt to revive the issue has been made since. The other possibility would be a merger with the City of Vancouver. This was proposed most recently in a 2006 Metro Vancouver planning report, but has otherwise also garnered little serious support.

The unique governance structure of the UBC-Vancouver campus remains intact. Almost a century after the campus and the University Endowment Lands were established as a separate entity, it is assumed that it has always been this way, and will be for the foreseeable future. Its origins – in a relatively minor political dispute decided by a small-town vote – remain largely unknown to students, staff, and residents alike.

Sources